100 - Life is Flimsy, Bow to Whimsy (Dhaka, Bangladesh)

I KNEW NOTHING OF BANGLADESH. Nada. Zilch. Zero. It may have remained so if not for the hand of fate. I met a group of Brits in Nepal on a Sun Kosi whitewater rafting expedition. I hit it off with a brother duo (Alex and Nick) and met up with them again for a prison adventure and then for the Gadhimai Festival). Alex was off to Bangladesh to meet a friend and suggested we connect for a foray into the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove swamp. When I learned this was also the stomping ground of the Royal Bengal Tiger, it was a hook, line, and sinker sort of deal.

I’d come up empty on a similar venture in the Sumatran jungle the previous year, and was more than willing to have another go. Alex’s enthusiasm matched my own, which cemented the decision to interrupt Operation: Nepal and head south. Bangladesh was a blind spot in my limited world knowledge—my ignorance an impetus, not a deterrent. Fortune, as they say, favors the bold… or the quixotically idiotic as it were. I was all in.

I phoned Bangladesh’s embassy in Kathmandu and was informed the visa process would take 15 days. The day I dropped off my passport, the clerk told me it would be ready that afternoon. I often find the reverse to predominate, so you can imagine my surprise at the expediency. Clearly, the universe was on board with my decision.

The visa fee was a puzzling $131 US. I later learned it’s a reciprocal “fuck you” to the United States, which sets a standard $131 fee for countries deemed potential problem areas in the immigration department. Foreign governments match the ludicrously random amount, even though many are more than happy to welcome American tourists. Never underestimate the influence of pettiness and juvenile retaliation. Then again, how the US came up with that specific figure (why not 130?) is beyond me and likely beyond anyone in charge.

A poster in Bangladesh’s embassy said it all: Come Here Before the Tourists Do. That’s not to say the country is devoid of foreigners, only that the vast majority aren’t tourists. Bangladesh is something of a developmental aid worker’s philanthropic wet dream with a heavy emphasis on microfinance. There’s no shortage of international organizations trying to shape and improve the country’s future. Henry Kissinger once labeled Bangladesh an international basket case. (Insensitive, much?) Sadly, it isn’t far off the mark and many a foreign NGO see the region as an ideal proving ground.

On the GMG Airlines flight from Kathmandu to Dhaka, I was upgraded to business class, no surprise for a man of my stature and obvious sophistication. Although “business” is nothing more than bonus economy, the extra leg room was most welcome. I got the feeling just about every westerner receives this upgrade, though I did spot a few expat souls languishing with mere mortals in coach.

In-flight entertainment included a dazzling light show projected through my cabin window. Much of Bangladesh is covered with alluvial plains resembling a toddler’s scribble drawing of rivers and streams. Through afternoon clouds and a thick ground haze, the landscape revealed itself in tiny vignettes. Reddish-orange rays of sunshine bounced across stripes of water as the sun shadowed our every move. Imagine watching a heart monitor while tripping on LSD or a psychedelic version of chain lightning. Beautiful. Hypnotic. Simple. An unexpected treasure that felt like mine and no one else’s.

I breezed through immigration with smiles on both sides and checked baggage in tow—an auspicious prelude. This made the taxi negotiation extravaganza an almost bearable enterprise. Fares started at “bend me over” and eased down to “gentle screwing.” I’m sure I could’ve done better, but I was pooped and had not the constitution for high-level talks.

I noted Dhaka’s air quality immediately, it had a taste and texture, especially at rush hour. Traffic is the typical “might makes right” unbridled chaos. Bumper to bumper. Snail’s pace. You know it’s bad when the driver shuts off his engine during stops. The smells. The sounds. The dust. The abject poverty. I won’t say it’s a log function increase from Kathmandu, but the contrast is sharp enough. A blind beggar felt his way from vehicle to vehicle. I pondered his evasive action plan after traffic started moving again, but didn’t get a chance to see the result. I’m guessing he relies on the kindness of strangers not to flatten him.

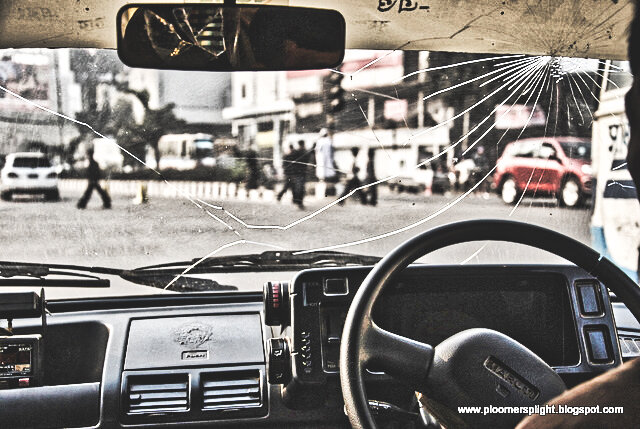

Buses, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and baby taxis swerve every which way while jockeying for position. Negative space is anathema. Fill it all. Gratuitous horn use is mandatory. Buses resemble recent contestants in a demolition derby—dents, chips, scratches, and missing parts provide ornamentation. I’ve read the accident rate is the statistical equivalent of “not if, but when.”

The taxi dropped me off at the Swiss Park Hotel, which would’ve been perfect if that was my intended destination. A friend recommended the Sky Park Guesthouse. I considered the possibility of a clerical error, so I went inside to investigate, only to discover it was a different hotel and out of my price range. Fortunately, Sky Park was nearby. Not only did the bellboy lead me to the other hotel, he carried my luggage. This brand of friendliness wasn’t out of the ordinary in Bangladesh. My enthusiasm dipped a smidge when the manager at Sky Park offered to help me get a SIM card at five times the going rate. Thank you, kind sir. Can’t all be peaches and sunshine. Still, the staff was and continued to be friendly and helpful, notwithstanding a hiccup here and there. The guesthouse made a fine Dhaka HQ.

Bicycle rickshaws abound. If you throw a rock in Dhaka, chances are you’d hit one. There are hundreds of thousands, if not millions of them. If you’re white and not in one, cabbies assume you want to be. Who the hell would walk on purpose, right? They were relentless, often shadowing me for blocks, no doubt in search of tourist gold. Most spoke little English and disliked discussing insignificant details like destination and price. They were more interested in assisting my presumed quest for beer, drugs, and hookers. If I were going to partake of any, I sure as hell wouldn’t do it in Bangladesh, a Muslim country. Though my fears of police entrapment a la a citizen’s arrest were likely overblown, I wasn’t taking any chances. My oft-repeated, “No beer, no lady, no drugs. I no smoke. I no drink. I no pay for lady,” did little to quell their determination to get me drunk, stoned, and laid. And yet, cruising around town on one of those suckers is good fun.

A step up from the pedaled version was the three-wheeled autorickshaw known as a “baby taxi” or “CNG” (Compressed Natural Gas). All the speed of an automobile with less protection. Claustrophobics beware. Imagine cramming into a caged escape pod and hurling one’s self into the breach. Caged, you say? Yep, though I’m not sure if it’s a crash safety precaution or a thief deterrent. Whatever the case, every journey was a hair-raising thrill ride.

“Close enough” is the most you can hope for when hailing any form of taxi. Between the language barriers and the haphazard street grid, it was a miracle I made it anywhere. Autorickshaws (CNGs) had the added quirk of often filling up soon after departure. I had the sense drivers lived paycheck to paycheck and didn’t have the funds to keep their ride topped off. CNGs had meters, but cabbies rarely used them… unless they filled the tank, in which case they’d leave it running. I found all this amusing as it only inflated the fare by cents. Not a big deal to me, but huge for them. I had no appetite to squabble over nickels and dimes.

The day after my arrival, a police officer explained why the streets were empty. It was Friday (Muslim holy day) and there was an Islamic festival unfolding, though I can’t recall the exact one. Empty? If by “empty,” he meant “not total anarchy” then I understood. There was still plenty of activity if glimpses from my cage were any indication. Still, it was nice to have less shit in my pants for a change.

How about a stroll? Nuh-uh. Sidewalks are subpar or nonexistent. More often than not, you’ll find yourself walking in the road, weaving between vehicles and rickshaws. Rickshaw drivers love to impede forward progress for a chance to exclaim, “Rickshaw?” At first, I tried a long disapproving stare, but this was ineffectual at best, antagonistic at worst. Better to eschew eye contact and keep moving.

Navigating Dhaka takes equal parts patience, fortitude, and equanimity. Shortfalls in any category will put a sizable dent in your sanity. This goes double for any trip over twenty minutes. I deemed a visit to Old Dhaka the order of the day one fine morning, so after breakfast, I explored transportation options. Rickshaw drivers wanted a king’s ransom for reasons that became clear later. It was an absurd distance for pedal power, requiring superhuman endurance and a death wish. I’d be bribing someone to destroy themselves physically while surmounting an absurdly dangerous traffic gauntlet as a bonus. Oops. Suicidal, much? Even by CNG, it was a forty-minute nail-biter through a dust-filled haze of disorder and folly. The driver wanted no part of the meter. It likely made the trip financially infeasible for the effort. Or it was a way to justify an inflated fare. Or both. Who knows? Either way, I was more circumspect about specific modes of transport from that point on. Greater distances required an automobile.

Old Dhaka had fewer automobiles, but an equal measure of compact chaos. The cramped streets swarmed with people and rickshaws, requiring a level of alertness that was downright exhausting. I was sideswiped multiple times, narrowly escaping injury. The streets weren’t well-marked, so if I needed to pause for orientation, I had to find shelter from the onslaught. My outdated edition of the Lonely Planet confounded my navigation efforts. I muddled about trying not to look out of place, an impossibility of geometric proportions. Would I have stuck out more if I’d been wearing a green sequin dress and a sombrero? Sure, but not by much. A white mutant wandering the streets in a confused fog isn’t something Johnny Bangladesh saw every day.

The following is a typical encounter between me and a stranger (typically male) on the street:

Bangladeshi: “Hello. How are you?”

Me: “I’m fine. How are you?”

Bangladeshi: “I’m fine. What is your motherland?”

Me: “America. USA.”

Bangladeshi: “Why you [unintelligible] Dhaka?”

Me: “Uhhhhh… just going for a walk?”

Bangladeshi: “Sorry, I don’t understand your response.”

Me: “Ummmm… sorry, what was the question?”

Bangladeshi: “Why you in Dhaka?”

Me: “Oh, I am tourist.”

Bangladeshi: “Thank you.”

Point gaze forward. Continue walking. Conversation over.

There were variations, but that sums it up. Strangers advanced, asked for a few details, and then skedaddled. I half expected a finger poke to verify my reality. I assume their curiosity extended only so far as their English. Stifling laughter took serious effort. Part of the problem was my look of perpetual bewilderment. Someone was always offering to help, and it was hard for them to comprehend I was walking about for shits and giggles. Children were cute and hilarious, asking to have their photos taken without expectation of reward.

*I accidentally deleted original photo files from my first few days in Bangladesh. I found low-resolution versions and used an “intense drama” template to hide my shame. Though a bit stylized, the tone and mood reflect (to a degree) the intensity of my experiences. The watermark is an earlier version of my site.

I’d planned to wander Old Dhaka’s streets for hours, but fate interceded. A man approached, introduced himself, and started to lead me… somewhere. I don’t know what he wanted to show me or what he thought I wanted to see. It didn’t matter because I was intercepted by students from Jagannath University. Their curiosity was infectious, and they were hell-bent on a campus tour. I hadn’t the heart to decline. Also, we were standing in front of the school. Resistance was pointless. Torun, a journalism student, cut the full tour short as he was impatient to showcase his office. Along the way, two more students joined the fray. The language barrier proscribed understanding, but it all seemed harmless. Intrigued, I adopted a “go with the flow” approach.

We flowed to his office where I fielded a fusillade of questions about, well, everything. Head spun. Photos snapped. Business cards handed out. Phone numbers exchanged. Victory Day headband adorned. Victory Day marks the country’s triumph over Pakistan in the 1971 Liberation War. I’d missed the festivities by three days.

The gentleman with the blue-white checkered sari had just emerged from the hole at the bottom of this photo. He had to completely submerge himself in what I can only presume to be the most foul-smelling nastiness imaginable to service a clogged drainage tunnel. Yikes.

Torun had work to do, but two of his compatriots offered a tour of the Ahsan Mazil (Pink Palace) built by a wealthy landowner in 1872. The palace held little of interest, but the cultural exchange was well worth my time. After a peek inside, we adjourned to the grassy area in front for a chat, a popular pastime for younger folks and “lovers” as my new friend put it. A second barrage of questions ensued, ranging from personal background to politics. Try explaining the US’s position on Afghanistan and Iraq in broken English to two Bangladeshi Muslims. Not awkward at all.

I was again the center of attention. People stared. Girls smiled. Strangers beckoned me forth for light conversation. My translators kept putting me on the spot with “Do you have question for them?” or “Ask him question?” while pointing at someone I’d just met. They referred to the less educated as “illiterates,” which I presumed meant no higher education. When one illiterate challenged me to a game of pool, I declined on advice of counsel and moved on.

We parted ways with a fond farewell and an offer to assist me in the future should the need arise. All I had to do was call. I was grateful for all they’d done and thanked them profusely. Yet, I can’t deny my relief on parting. Such cultural exchanges are extremely rewarding but psychologically draining, a constant struggle between comprehension and situational awareness. I needed to recharge.

Futility in the face of extreme poverty is a stressor all on its own. I’d experienced it before, but it hit me hard there. I passed individuals living on the sidewalk near a park, belongings spread along the wall separating the two. One gentleman lounged on a cardboard mat as if not having a care in the world. The incongruity between expression and plight was striking. He asked me to take his picture, so I obliged. His delight in seeing his visage on the small LCD seemed genuine, which somehow injected even more pathos into the scene.

I almost felt good about the exchange when I noticed an undersized toddler under a blanket lying on the ground. I presumed the child was sleeping. I really hoped the child was sleeping. His eyes were closed and covered with buzzing flies. I took another thirty steps and paused, feeling like I’d been flattened by an emotional steam roller. I stood staring at the sky, holding back tears. The intensity caught me off balance. It wasn’t the tragic scene, but the futility attached that floored me.

What could I do? Distribute cash? Hand out groceries? I considered random acts of charity but declined in the end. Would it even benefit that child? Whose child was it? Who should I give the money to?… Futility. So, I kept walking. The haunting continues to present day.